In what Casetext cofounder and CEO Jake Heller calls a breakthrough that will have a profound impact on the practice of law, the legal research company is today launching Compose, a first-of-its-kind product that helps you create the first draft of a litigation brief in a fraction of the time it would normally take.

In a preview demonstration given under embargo during the recent Legalweek conference in New York, Heller showed how he could use Compose to create a first draft of a brief in five minutes.

The product, the company says, “is poised to disrupt the $437 billion legal services industry and fundamentally change our understanding of what types of professional work are uniquely human.”

Heller and cofounder Pablo Arredondo, who is Casetext’s chief product officer, say this is the first brief automation product in the legal market and only the second litigation automation product, after LegalMation, which automates the creation of responsible pleadings in litigation.

Casetext is a company that is known for developing innovative legal research products. Its brief analysis product, CARA, launched in 2016, was recognized by the American Association of Law Libraries as product of the year and has spawned a spate of similar products.

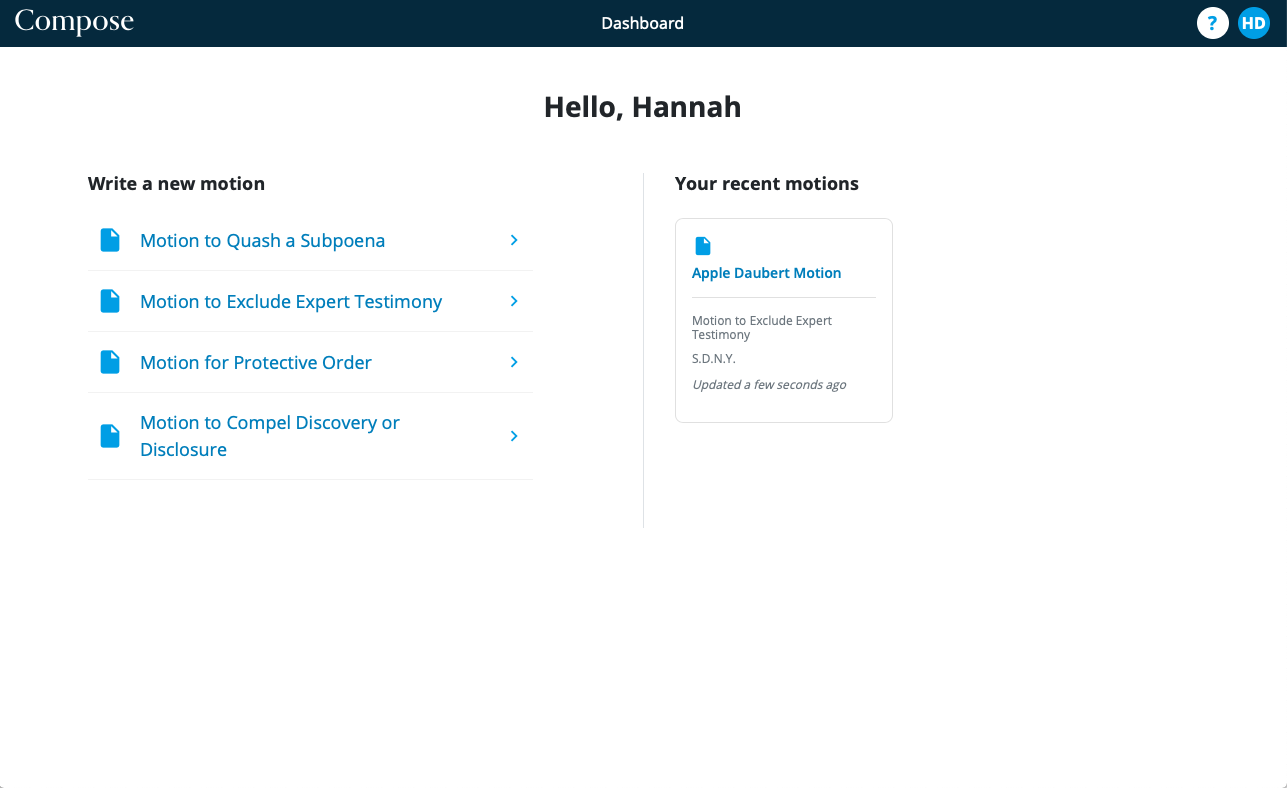

Compose is not for writing appellate briefs. It is designed for writing litigation briefs in support of standard procedural motions, such as a motion to exclude expert testimony or a motion to compel discovery. It can be used only for the specific types of motions the product covers, which Casetext will be building out over time.

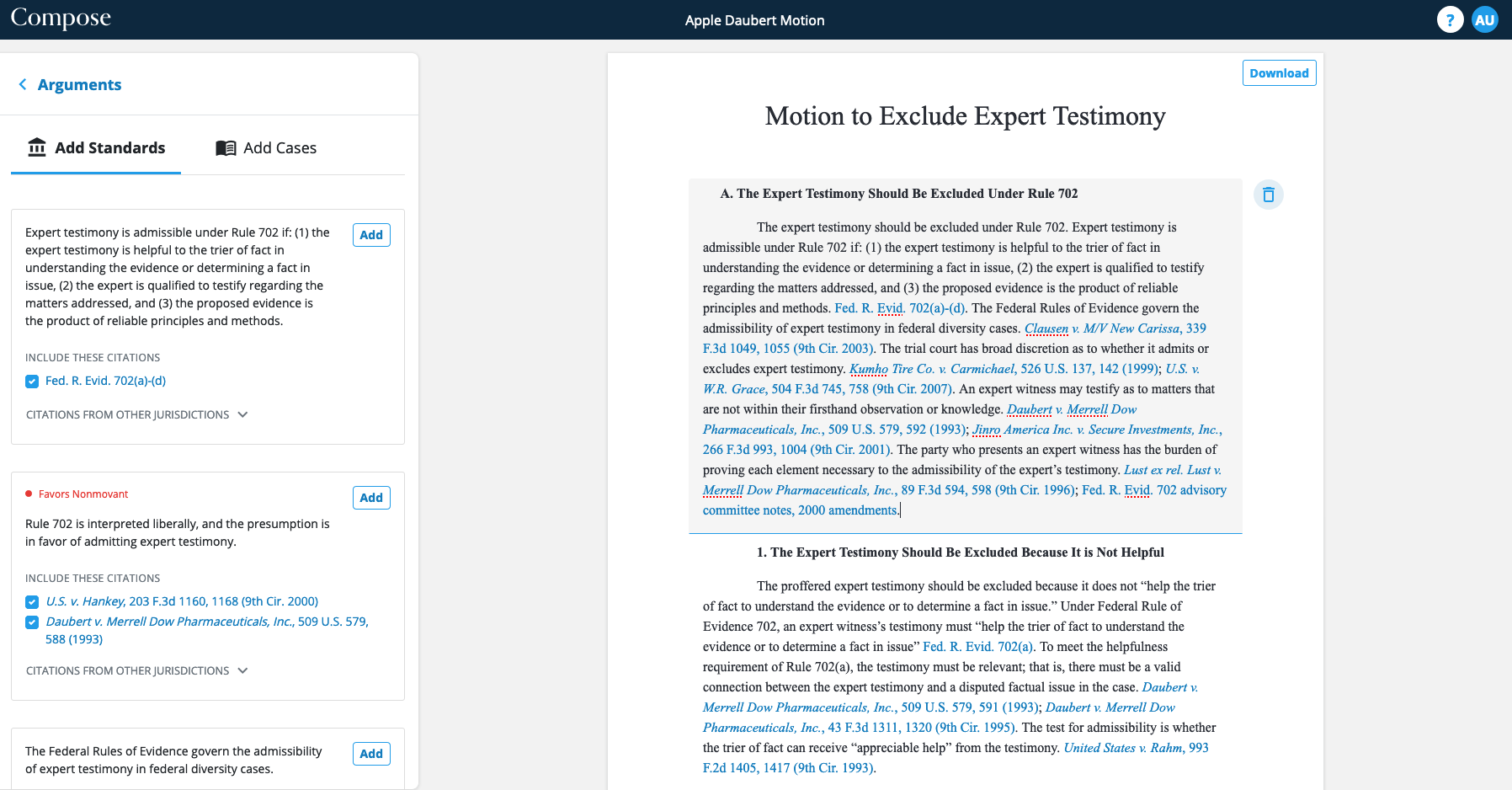

Arguments and Legal Standards

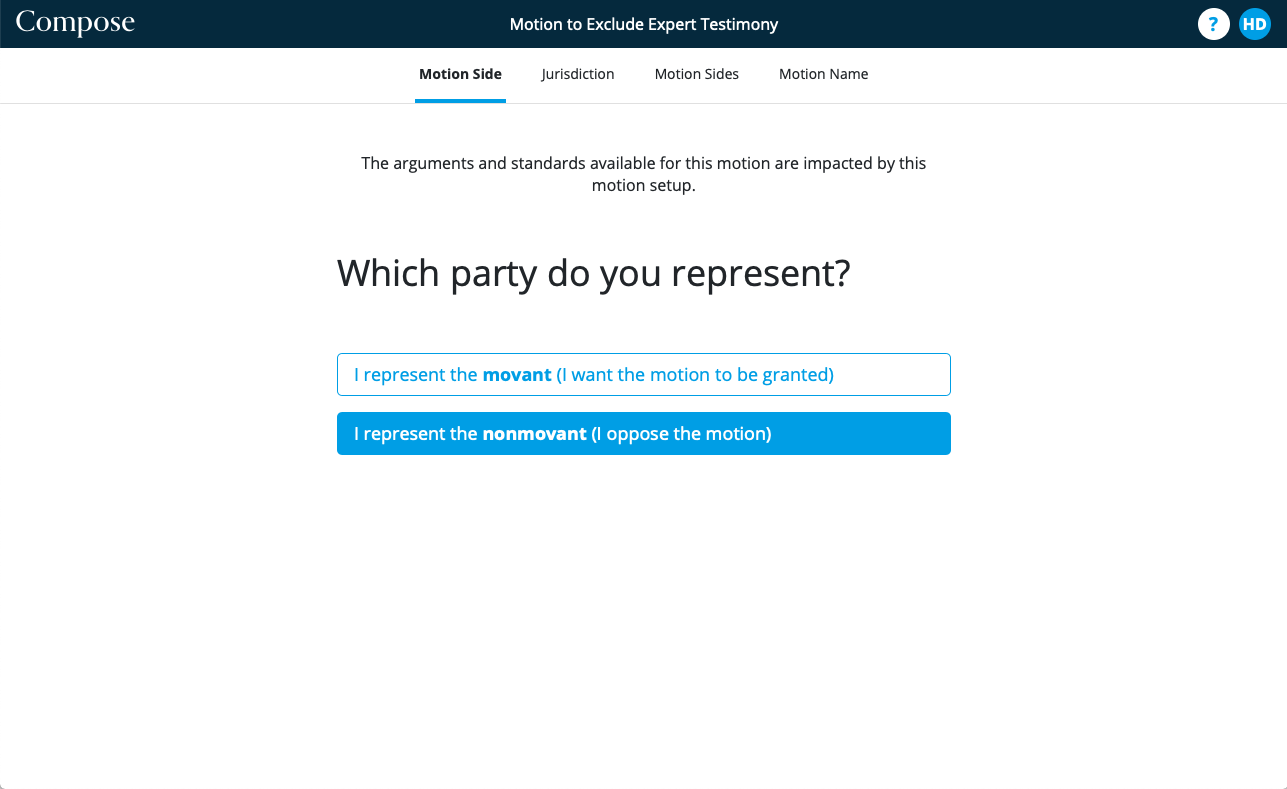

To use Compose, a lawyer begins by entering basic information about the brief, such as the nature of the brief, the jurisdiction, and the lawyer’s position for or against the motion.

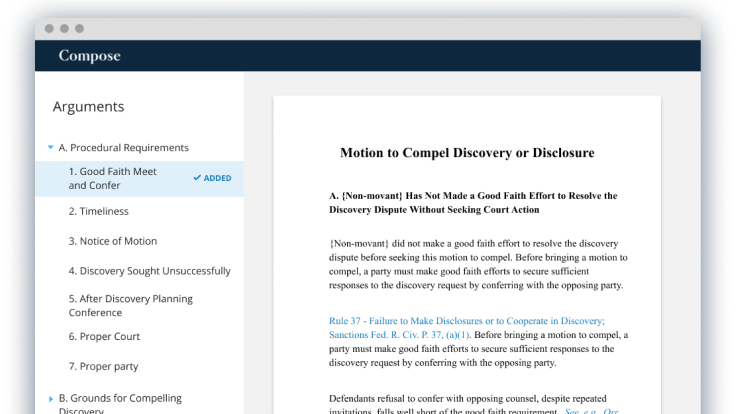

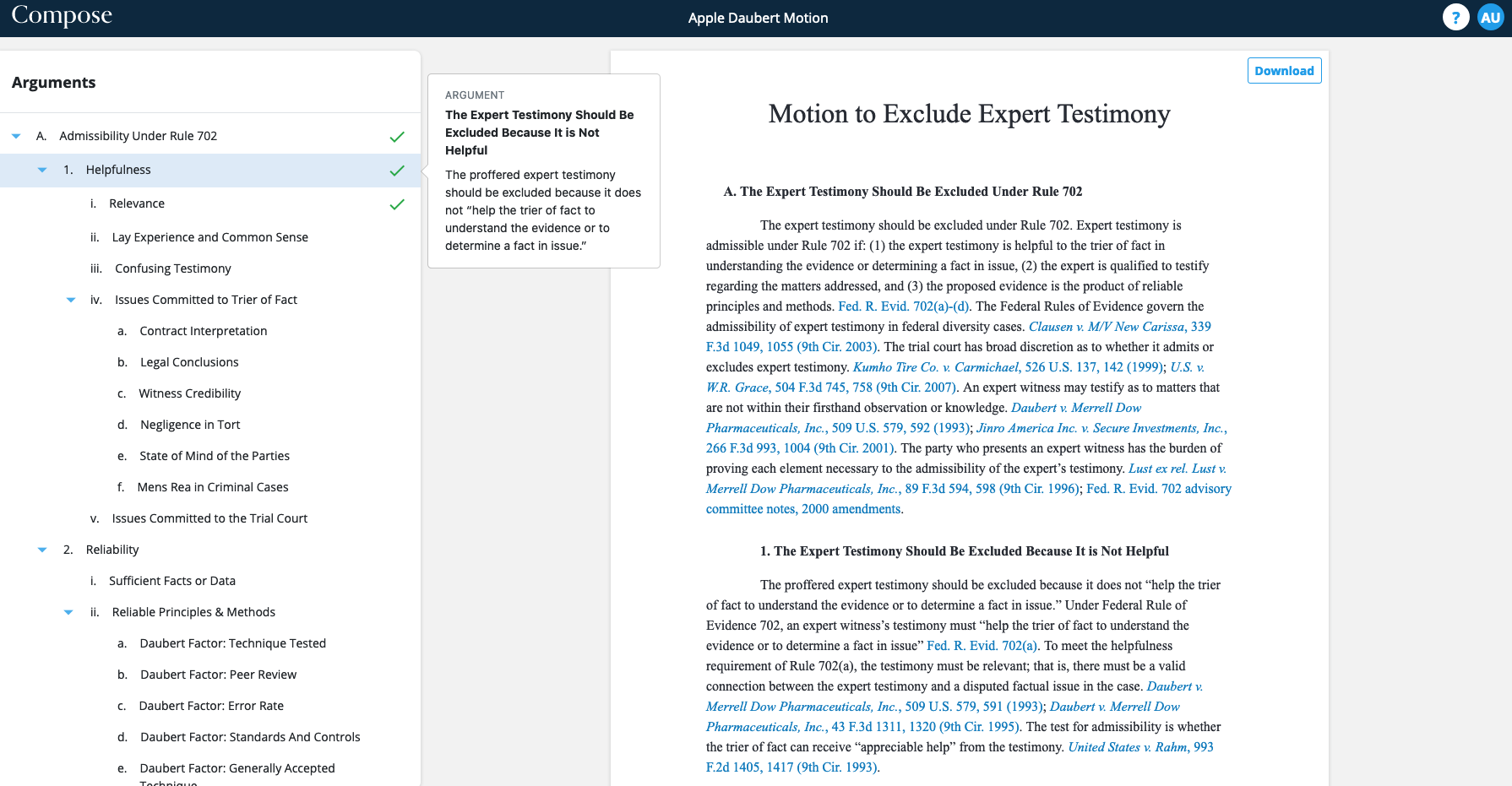

Compose then presents the lawyer with a treatise-like outline of what Casetext says are all the available arguments for that motion, as well as the legal standards or rules applicable to each argument.

The lawyer simply peruses the available arguments and standards and then clicks on a standard to add a fully composed paragraph to the brief that states the rule, including citations. The text is fully editable, either within Compose or later when the draft is exported to Word.

“Picking arguments to add to your brief is like choosing pastries at a French patisserie,” Heller said during the Legalweek demonstration.

The legal standards that Compose suggests are tailored to the jurisdiction and state identified by the lawyer, Heller said. Arguments can be nested hierarchically.

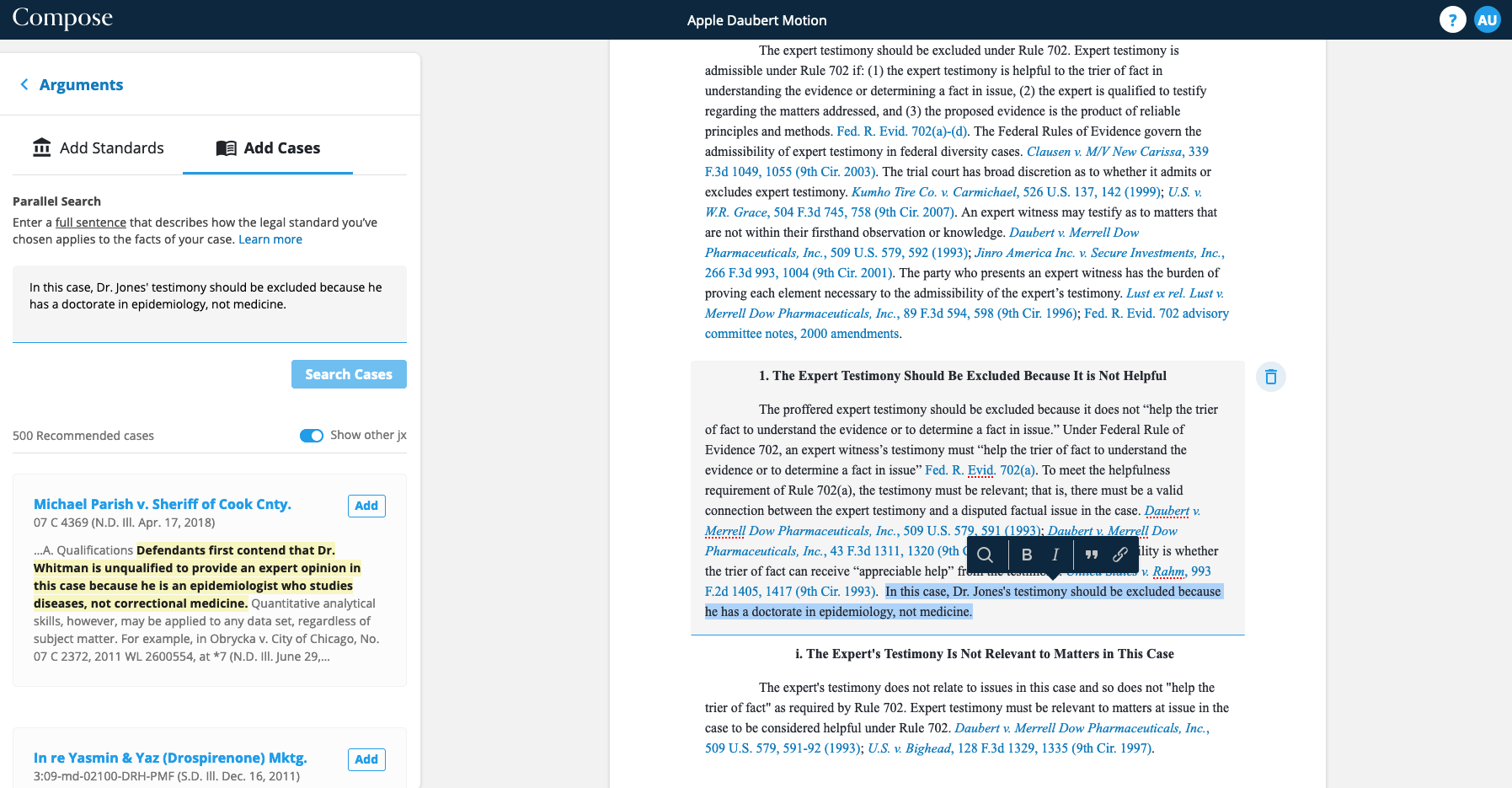

Parallel Search

If offering that selection of pastries was all Compose did, it would be notable of itself. But a second feature of Compose takes it further, not only suggesting pastries, but feeding you the full menu.

Called Parallel Search, it uses advanced natural language processing to follow you as you draft your arguments in the brief and automatically provide you conceptually relevant precedent. Notably, Casetext says this works to find analogous caselaw, even when the cases do not use the same language.

“This fills in a blind spot in current search,” Heller told me. “It allows you to return cases that have a violently different articulation of the current concept.”

At the Legalweek demonstration, Heller gave an example by typing the argument, “Plaintiff’s testimony was deceitful.” Parallel Search returned a case in which the judge concluded that testimony was “frankly incredible.” The algorithm understood that deceitful and incredible were parallel concepts.

As another example, Heller typed the argument, “Target is liable for not cleaning up the banana peel that Ms. Jones slipped on, injuring her hip.” Parallel Search returned a reference to a case that said, “Davis alleges that Kroger’s employees were responsible for negligently leaving a soapy substance on the ground that caused her to fall.”

Types of Motions Covered

Compose’s motion automations will be offered as collections. The first three collections to be marketed will be Federal Discovery, Federal Motion to Dismiss, and Federal Core Civil Procedure. As of today’s launch, there are six motion automations available:

- Motion to Compel Discovery.

- Motion to Quash or Modify a Subpoena.

- Motion for Protective Order.

- Motion to Exclude Expert Testimony.

- Motion to Dismiss for Failure to State a Claim

- Motion for Preliminary Injunction

Over time, Casetext will release new motion automations and collections.

What It Costs

Casetext will sell Compose as a separate product from its legal research service. Six larger law firms have already signed on as customers: Ogletree Deakins, Sheppard Mullin, Bowman and Brooke, and three others that Casetext declined to name.

For solo and small-firm attorneys, they will be able to purchase Compose on an a-la-carte, per-brief basis. The first use will cost $99. After that, each brief will cost $1,499.

For larger firms, they will purchase Compose on a subscription basis. Subscriptions will be offered based on bundles or themes, such as federal discovery or federal civil procedure.

Heller envisions that firms will purchase some subscriptions on a firm-wide basis and others on a practice-specific basis.

Casetext will also sell Compose to clients, such as insurance companies and inhouse legal departments, on both a single-use basis and in packages allowing a certain number of briefs.

The Bottom Line

Heller said that compose will allow lawyers to write better drafts of briefs in as much as one-tenth the time it would typically take. Given that litigators spend more than half their time working on motions, that could be a significant savings.

But lest anyone label this a robot lawyer, let us be clear: You still need to craft the brief. Compose gives you a shortcut to assembling the skeletal framework of legal principles that support you, but it remains your job to add substance to that framework and weave it all together into a compelling argument.

But even there, Compose’s Parallel Search feature will help, delivering up cases that are conceptually similar to the facts of yours and providing the fodder you need to support your positions (or highlighting the cases that work against you).

“Compose commoditizes the parts that lawyers never liked working on and clients never liked paying for,” Heller said. “At the end of the day, what’s left is the lawyer’s imagination, creativity, intelligence and persuasiveness in the brief-drafting process. That’s what we’re excited about.”

I have not used Compose directly. I have seen it demonstrated twice. Based on what I have seen, I have to agree with Heller that this appears to be a breakthrough technology for legal professionals. Just as Casetext’s competitors scrambled to emulate CARA, I suspect they will now scramble to come up with a Compose product of their own.

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog