In what it says is a first for artificial intelligence contract-analysis platforms in the legal industry, Kira has developed a differential privacy algorithm that protects the confidentiality of text in model training data when a user shares a machine-learning model with other firms or organizations.

The differential privacy algorithm prevents an attacker from potentially being able to reverse engineer or infer words from training documents, and thereby reveal confidential client information. It is applied each time a smart field — a machine learning model within Kira — is shared with others using a feature called Smart Field Sharing.

“Our Differential Privacy algorithm is an essential capability that helps lawyers confidently meet their professional responsibilities of confidentiality to their clients, while also unlocking the ability to offer new service delivery models,” a company statement says.

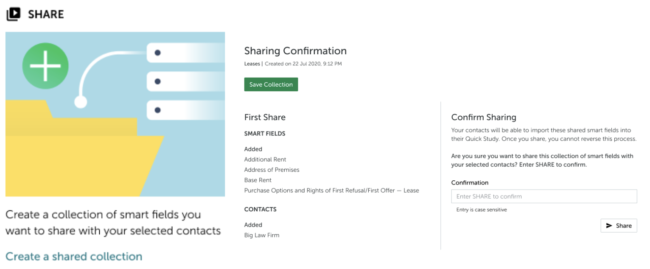

“With Smart Field Sharing, lawyers and other professionals can collaborate on AI-assisted contract analysis with those in other organizations to deliver contract analysis needs, with confidence that an adversary cannot reverse engineer any confidential data from Kira’s smart fields.”

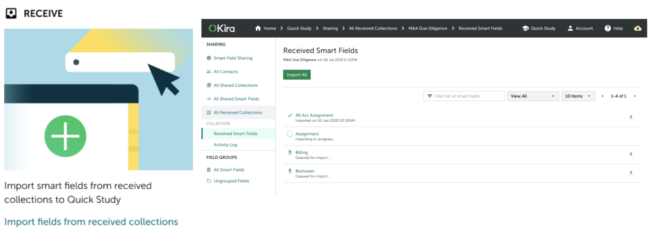

Kira allows customers to share smart fields outside their organizations.

During a preview last week of the new capability, Steve Obenski, chief strategy officer, and Alexander Hudek, chief technology officer and developer of the algorithm, said that this is an added layer of security, because Kira’s models are already architected in a way that ensures they contain no words or text, so that sharing them does not of itself expose confidential information.

But while Kira comes with over 1,000 machine-learning smart fields that identify common clauses and contract provisions, customers can also use a feature called Quick Study to create their own custom smart fields by training them on their own documents, including confidential documents.

If a customer wants to share a custom smart field outside its organization, someone could conceivably combine information collected from other sources to infer what the text might have been.

Users can share collections of smart fields.

A simple example provided by Kira is that if a smart field works better on New York commercial leases than it does on Los Angeles residential leases, then someone might infer that the original documents used in the training data related to New York commercial properties.

Hudek calls it an inference attack, in that the attacker would never know for certain that a particular word or phrase was used, but could infer it.

“We wanted to be able to say we can guarantee that it is safe to train an AI model and then share it safely,” Obenski said.

Another example given by Obenski is of a lawyer specializing in hospital mergers who uses data from past transactions to train a smart field on patient rights requirements. The lawyer could share that patient rights smart field with a client, the acquiring hospital, which might use it for purposes of not just post-merger integration but also ongoing compliance.

“This smart field could continue to do its work even when that lawyer who originally trained it is not around,” Obenski said. “This ‘virtual secondment’ of that lawyer’s knowledge and experience to the client hospital offers an entirely new service delivery model that simply wasn’t possible before now.”

“Confidentiality is a cornerstone for relationships between law firms and their clients,” said Hudek. “Differential privacy is the only technique available today that can guarantee the privacy required by law firms.”

Robert Ambrogi Blog

Robert Ambrogi Blog